“What to do when a safe space becomes hell?”

“What to do when a safe space becomes hell?”

After Spanish director Patricia Franquesa’s personal photos ended up in the hands of a cybercriminal, her life changed forever. But instead of remaining silent, she picked up a camera — and turned her pain into the film My Sextortion Diary. In a candid conversation for the Travelling Docudays UA, Patricia shares how a personal tragedy became a story about courage, self-healing, and the power to say “no.”

Patricia, what inspired you to tell this deeply personal story?

It all started on August 1 — that was the day I found out I had become a victim of blackmail. The next day I went to the police. They said there wasn’t much they could do but advised me to send an email to all my contacts, warning them that a virus was allegedly being spread from my account, so they shouldn’t open any emails with photos.

While writing that message, I began to research the topic and suddenly realised I wasn’t alone. This happens to companies, to ordinary people — all over the world. And then I thought: I’m a documentary filmmaker, I have to tell this story.

The second important moment came when I realised how painful it was. If it was so hard for me, an adult woman, to cope with the shame and fear, what must teenagers feel? I realized that I had to make this film — not only for myself but also for others who might find themselves in a similar situation. Photo: still from the film “My Sextortion Diary"

Photo: still from the film “My Sextortion Diary"

How difficult was it to return to such a painful experience during the filming?

It was painful, but at the same time healing. My capacity for emotional detachment helped me — I used my own body and emotions as a tool. When I cried during editing, I realized: this moment must stay in the film.

I reread old correspondence, created spreadsheets where each sheet represented a day of the blackmail, with all the messages from friends, family, and the police. It was difficult to see myself from the outside, to notice my own mistakes, my reactions, even the moments when I didn’t always listen to my friends. But it was precisely this honesty that made the film genuine.

How did you decide on the visual style and tone of the film?

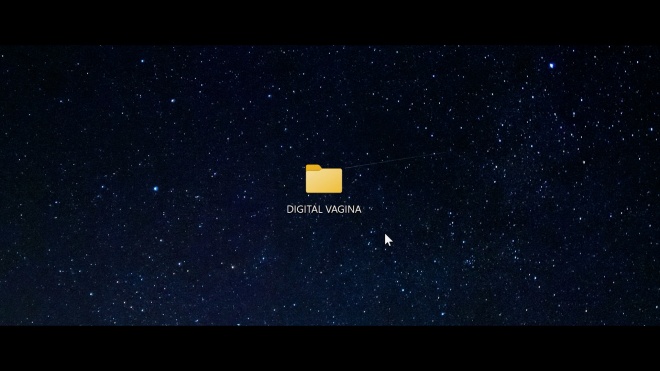

From the very beginning, I knew I wanted to make a film composed entirely of digital elements, the things the hacker had access to: my messages, videos, photos, work materials. It’s like a journey into the digital memory of a person who has been hacked.

I wanted the viewer to feel as though they were spying on me. The film became a kind of experiment about the boundaries of privacy: what is more intimate, seeing my body or seeing my inner world through messages, notes, memories?

People often told me that this format wouldn’t work for a feature-length film. But I believed in my idea. And now I’m proud that we were able to bring it to life. Photo: still from the film “My Sextortion Diary"

Photo: still from the film “My Sextortion Diary"

What was the response of major platforms such as HBO or Netflix?

We had negotiations, they were interested in the film, but at the same time wary of the format. During the pandemic, everything was happening online, and perhaps my energy wasn’t conveyed through the screen. I’m sure that if the meeting had been in person, the film would have been purchased. But even without that, I’m happy: we made exactly what we intended to.

What are your hopes regarding the film’s impact on young people and potential victims of cybercrime?

The most important thing is that people watch the film and then say, “I saw a film about a girl who was blackmailed, and she made a film about it herself.”

My goal is to show that there is a way out. Even if you made a mistake, trusted the wrong person — you are not to blame. Asking for help is not shameful, it is strength.

I screen the film in schools, and every time I see that young people understand how important it is not to stay silent. Once, after a screening, a boy told me that I had “done the wrong thing.” And I replied: perhaps. But the main thing is that I survived. And I want others to know: there is always a way out. Photo: still from the film “My Sextortion Diary", Patricia Franquesa

Photo: still from the film “My Sextortion Diary", Patricia Franquesa

What would you tell those who are afraid of the digital space after your story?

I love the internet and technology. But it’s important to be aware that a safe space may turn into hell.

So we need to be cautious, but not live in fear. We’re all part of this digital reality, and we must learn how to protect ourselves in it — and how to support one another.