Hero Riders: how do Ukrainian and Italian delivery services work during COVID-19?

Hero Riders: how do Ukrainian and Italian delivery services work during COVID-19?

Riders Not Heroes of the pandemic — mythology, fears, and adaptation to the new reality. What human rights we had to waive in exchange for health care and the comfort of society was discussed at the final discussion of this year’s Docudays UA trip to Lviv Region. Conversation participants: Artem Kovalevskyi, a participant of the strike of riders, Maksym Romaniuk, a former Glovo rider and Ilia Vlasiuk, a member of the Club for the Study of Precarious Work («Гурток з вивчення нестабільної зайнятості»). Yosh, head of the Feminist Workshop NGO moderated the discussion.

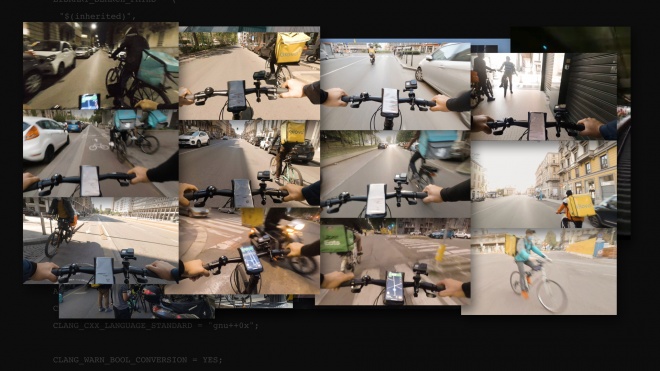

Riders Not Heroes is a short video essay by two Italian directors, Davide Rapp and Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli. The main characters of the film are food delivery riders in Milan, armed against the COVID-19 with motorcycle helmets and paper food packages.

The fourteen minutes of the documentary are based on two main metaphors: the technological emotionlessness of the robot announcer and the process of human digestion that does not stop during coronavirus pandemic, revolutions, or bubonic plague. A mechanized voice indifferently accompanies the path of a rider delivering food in neat paper bags around Milan affected by COVID-19.

The voice talks about platform capitalism, the gig economy, the refugee crisis, labour rights, and a handful of people on bicycles or motorcycles who get on their routes every day. The depiction of the digestive system at the end of the film reminds us that the process of social digestion cannot be stopped, even if the most precarious groups dissolve in the acidic environment of a new disease.

“When one of us gets into an accident, everyone thinks, "Well, what can you do? It's a delivery rider,” says Artem Kovalevskyi. Artem is currently working at BoltFood delivery service. Comparing the Italian and Ukrainian realities, Kovalevskyi explains that if in Italy mainly illegal migrants or students work as riders, the situation in Ukraine is different. Ukrainians mostly work legally, and the income level of a rider who works 8-10 hours a day can approach or exceed the earnings of a middle-level office worker. According to Artem, the European level of payment for this work is much lower.

However, nowadays salary is lower, which led to a strike of riders:

“In August, our income was cut by 30-40 percent. So one of the main demands of the strike was returning past salaries. Of course, it was important to reduce the waiting time at the restaurant door to get the order, and to remind companies about the insurance — most riders do not even know that they are entitled to it. However, the main issue is the income level.”

Artem believes that all the costs of the rider's work (repair of transport equipment, physiotherapist services because the work requires extensive physical training and physical activity, should be compensated financially. Bonuses from the company, such as corporate English courses, are a nice thing. However, no one knows better than the rider what is a priority for him- or herself now — technical maintenance of the bike, the back stretches in the pool, or work on the pronunciation of foreign words.

Platforms used by riders also require optimization. The system is becoming less sensitive to changes in weather patterns. On the one hand, income becomes higher when the weather is worsening outside. However, the system takes into account the blizzard and rain but ignores the bright summer sun, which hurts the eyes.

Maksym Romaniuk, a former Glovo employee, started making money as a rider during quarantine after a public service burnout. The position was attractive: the simple employment procedure, the lack of complex diversified responsibilities and accountability to corporate work, a flexible schedule, and the opportunity to work as much as he can and wants each day.

“There were no special COVID-19 warnings. The only thing is that at the beginning of the quarantine the rider could claim financial compensation in case of infection. For me, physical activity was the advantage of this job — not everyone had this opportunity during a strict quarantine. Of course, one could hardly find this job an easy one — it is quite difficult to ride a bike for 10 hours. For many, a week spent recovering from muscle soreness is the last one.”

As for the prospect of career growth — it does not exist. Maxym says that the scheme of the rider's work is completely different: he travels the city along the same roads, and at first, it is very interesting to look at them. But over time, this work turns into a sad and tedious activity, and the rider loses the desire to work. His colleagues gradually returned to their previous jobs which were already formalized. Few people consider this job permanent.

Ilia Vlasiuk, a member of the Club for the Study of Precarious Work, considers the "uberisation" of the labour process to be a rollback to early industrial types of work — no social functions of the state, insurance, labour guarantees, and employer responsibility:

“It is unlikely that Italian legislation would allow aggregator companies to work the way they do in Ukraine — the employment relationship is not formalized here. Delivery riders are not affiliated with their employers (legally ed.), they are considered "software users". In better-off countries, this is not considered normal.”

Vlasiuk explains that the benefits of organizing the work of riders through platforms are debatable. The position of aggregator companies manifests in the slogan: "We just connect contractors and customers for a small commission." However, the real situation is different.

None of the riders know what wage ratios the system will calculate. The platform itself appoints the rider for an order, sets the conditions according to which employees can shape their work schedule. Thus, companies avoid taxation and violate the law: the costs are borne entirely by employees, and the aggregators receive a net income. This is not a job you can put in your resume, it won't allow you to earn more, and it doesn’t count towards your work experience.

In Ukraine, the first insurance for riders was introduced after the protests of Glovo employees in Kyiv in 2019 — before that, the company avoided it in every possible way. Vlasiuk emphasizes that bonuses and guarantees do not grow on trees, you have to fight for them and protect your rights.

At the end of the discussion, participants made several suggestions for improving the working conditions of riders. Artem Kovalevskyi shared the idea of creating a community of riders that could defend its rights and engage in mutual assistance. Rider's work can also help spread information about charity, civil protection, and other similar initiatives because employees often interact with other people. Artem is working on the introduction of electronic tips so that people can support the riders: some platforms have already launched this option, but the customer must specify the amount of tips in advance, before receiving the order. Kovalevskyi emphasized the importance of guarantees related to the compensation for road conditions — at least 100 or 150 UAH per hour.

Ilia added that the delivery labour market would feel much better if more businessmen and businesswomen had access to it. More competitive conditions in the field would force employers to be more conscientious in their responsibilities. In particular, employment contracts with an unfixed work schedule would solve the problem of the absence of official employment and regulate the relationship between riders and aggregators.

“The labour market is oriented at lower-level standards: if the number of people working in poor conditions for many hours grows, then it happens in other areas”, said Ilia. “We can all fall under “uberisation” with no guarantees. That's why we have to fight precarity and work together to improve the situation.”

You can watch the discussion here.

Text: Alyona Martyniuk

Photo from the page of Labor Initiatives CBO

Stills from Riders Not Heroes