Docudays UA Park and Prominent Figures: Travelling Festival through the eyes of Volodymyr Khanas

Docudays UA Park and Prominent Figures: Travelling Festival through the eyes of Volodymyr Khanas

The final article in the series of memories about the 20 years of the Travelling Docudays UA is a conversation with a person who carefully collects hundreds of materials about the Docudays UA International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival in the storage of the Kremenets Local History Museum. Volodymyr Khanas is the festival’s regional coordinator in the Ternopil Region, film producer and public figure. We want his metaphor for the “image of the future” and the actual Docudays UA park to resonate with each of us. But first, the future is impossible without exploring history.

In this article, read emotional recollections of prominent figures connected to the festival and learn about the paradoxes of documentary cinema.

What is your brightest memory that immediately comes to mind when you are asked about the festival’s history?

Each memory of the festival for me is about people whom I cannot forget. It was 2008, maybe 2009. Back then the preparations for the festival in Kyiv were organised by a team led by the late producer Andriy Matrosov. I was walking behind the scenes of the House of Cinema and saw two volunteers, the twins Oksana and Maryna. Back then they were very young, and I remember their ponytails. I climbed the ladder and helped them hang a banner. They were very active volunteers, interested in everything, and much later, in 2018, they were the ones who gave awards to the festival winners as recognized filmmakers. I watched it and recalled the ponytails next to the ladder. I still follow the work of the Artemenko sisters closely, they make great films, write scripts and participate in international festivals. For me this is a symbol that when people have a lot of aspiration and inspiration, they can reach the top. This is a reflection of Docudays UA.

Oksana and Maryna Artemenko at Docudays UA in 2019

I also recall with admiration the coordinator from Kryvyi Rih, a renowned environmentalist, human rights advocate and the head of the Kryvyi Rih Prosvita, Mykola Ivanovych Korobko. He was a very modest person despite his status, to the extent that he never even told anyone that he was an MP in the first convocation of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine. Some new regional coordinators had no idea that this “grandpa,” who was always inquiring about something or clarifying something in detail, was a true hero whose spirit is as strong as the spirits of the people we see in documentaries.

And one night, at a meeting of regional coordinators, I asked Mykola Ivanovych to stay with us at a dinner party, although he was very modest and anxious about how he would feel in a circle of “youngsters.” And I told everyone, “Do you know who our colleague is? He’s a living hero, MP in the first Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine who won the election in Kryvyi Rih in 1990, a member of the People’s Council who voted for the Independence Act. You should have seen that pause. Everyone was asking, “How do you mean? Mykola Ivanovych? The man we’re all so used to?” I would say that this person can be an example of a people’s elected official. He cared about how his neighbours lived, how his city lived. He advocated for his vision of protecting human rights and our nature.

Mykola Ivanovych Korobko, one of the first creators of the Travelling Docudays UA International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival

How did it all begin for you with the Travelling Festival?

I first joined Docudays UA in 2007 at the House of Cinema. I was invited there by the late Illia Fomenko. Then I met Gennady and Igor Kofmans, I saw members of the UHHRU and the Renaissance Foundation whom I’d met before, but not at the film festival. Maksym Butkevych, our colleague, human rights advocate and soldier who is now in russian captivity, was a jury member. That year, the festival gave an award to the film Femida, a Loose Woman by Viktor Dashkevych, which reflects on the problems of a court system in a totalitarian state. I remember that we were already discussing the creation of the Travelling Festival in my region and the development of the dialogue about human rights. We made an attempt in 2007 as well, but in a small circle of viewers. Interestingly, children born in those years are already the festival’s fans now. It was the beginning of my cooperation with Docudays UA, and already in 2008 I screened films from the Travelling Festival’s programme in Ternopil together with Oleksandr Stepanenko, our friend and partner of many years from the Chortkiv environmental NGO Green World. I must also mention Alla Tyutyunnyk. Imagine reading her story Further than an Arrow Flies in a magazine back in 1988, being fascinated by the text, and then, in 20 years, becoming her festival partner!

How did the first festival in the Ternopil Region go? What was the audience interested in? What did you talk about back then?

We had rather good starting conditions. Back then I was working as a deputy director of the Dovzhenko Centre for Leisure and Youth Initiatives, it was a former cinema. We had no problems with the venue.

Films were occasionally screened there, mostly non-commercially. Sometimes the audience hall of 300 seats was full, and sometimes there were just four or five dedicated fans. There were few Ukrainian films among the Travelling Festival’s first screenings, one or two. The audience wanted to see Ukrainian documentaries. And we were growing rapidly in this regard. Today the DOCU/Ukraine competition is very intense. It has also included films in whose creation I personally participated later (Maria, Bars. Unfinished Story, Frontline Life, Rosokhach Group). We’ve managed an enormous breakthrough in documentary cinema in general and in human rights documentaries in particular here in Ukraine.

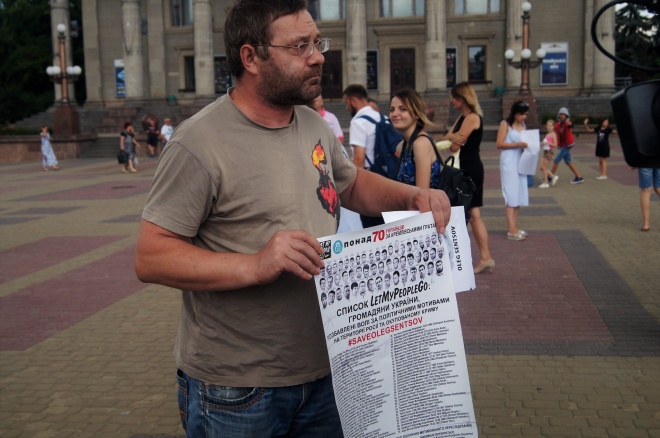

Volodymyr Khanas at a human rights demonstration, from the interviewee’s archive

How has the Travelling Festival affected your decisions in the professional field, and maybe also in your personal life?

In 2016, the former head of the Ternopil Film Commission called me and asked me to join his institution as an expert. It happened thanks to my festival experience. Since then, I started receiving requests regarding consultations about cinema not only from Ukraine but also from other countries. After some time, I became the head of the Ternopil Film Commission. The Travelling Festival is an enormous experience, both professional and personal. You can practically learn anything at Docudays UA if you’re just willing to learn. I dare say that it’s an elite film university. The festival also has a strong communications network which is important for the whole Ukrainian history of film production. In the end, its people are something that’s indispensable.

I’ve had to promote a few documentaries, and my festival contacts, professionals who have worked in this field for a long time, really helped me in this task. They do not just know their work, they even take into account the option of “how the mood of the cinema director or the school head teacher changes” when they plan the screenings. It’s actually fantastic when you have an opportunity to do your job and combine it with the Travelling Docudays UA. The best kind of job is a “high-paid hobby.”

Please tell me about your Travelling Festival during the Maidan, what was it like?

The poster of Docudays UA 2013, from the collection of festival memorabilia by Volodymyr Khanas

Sometimes a film makes history. In the producer community, we always try to figure out the secret of success for various films, but often something unpredictable happens. We joke that sometimes you need “secret forces you don’t know of” to work for you.

During the Maidan, there was an almost anecdotal story about this in particular. We were preparing for the Travelling Festival, we had a list of films. One of the most high-profile films was the one about Yanukovych’s mansion in Mezhyhirya. We began in October. Then weird things started happening in different regions: cancellations, “bomb threats” in Frankivsk, confrontations with the Security Service and local authorities.

We finished the Travelling Festival in the Ternopil Region before the events of the Maidan, and in winter all of our colleagues, activists and volunteers were already in Kyiv.

Interestingly, in late December a friend of mine who’s a police officer told me, “You know, they sent me this film from Kyiv, it is banned, but if you need it, I’ll show it to you.” It later turned out that it was the same film on Mezhyhirya from the Open Access almanack. It was shared peer to peer in secrecy, even though you could have come and see it openly at our festival.

Sometimes a film makes history. In the producer community, we always try to figure out the secret of success for various films, but often something unpredictable happens. We joke that sometimes you need “secret forces you don’t know of” to work for you.

During the Maidan, there was an almost anecdotal story about this in particular. We were preparing for the Travelling Festival, we had a list of films. One of the most high-profile films was the one about Yanukovych’s mansion in Mezhyhirya. We began in October. Then weird things started happening in different regions: cancellations, “bomb threats” in Frankivsk, confrontations with the Security Service and local authorities.

We finished the Travelling Festival in the Ternopil Region before the events of the Maidan, and in winter all of our colleagues, activists and volunteers were already in Kyiv.

Interestingly, in late December a friend of mine who’s a police officer told me, “You know, they sent me this film from Kyiv, it is banned, but if you need it, I’ll show it to you.” It later turned out that it was the same film on Mezhyhirya from the Open Access almanack. It was shared peer to peer in secrecy, even though you could have come and see it openly at our festival.

What changed for you after the events of the Maidan?

In 2014, I returned from Crimea, where I was the head of a monitoring group observing the so-called “referendum” for over 2 weeks. After that, I came for a day to the Euromaidan Forum in Uman. Then I visited the Docudays UA festival. We discussed the fate of Crimea a lot back then. In March, we had a press conference in UNIAN and we were unable to realise and say out loud that the war had begun. I mean, there was a kind of vision, feeling, understanding, but we were unable to articulate it in detail. We relied on international law, influences. We determined that it fits the UN Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, namely “partial occupation.” But talking about constitutional human rights and freedoms was impossible. Only people with assault rifles had the rights.

At that point we realised what kind of people were the many documentary filmmakers with russian passports who were happy to visit Ukraine, including Docudays UA. And they liked it here, they were glad, but in 2014 many of these “citizens” simply did not react in any way, and since the beginning of the full-scale invasion they actually revealed their positions very clearly. There is no more room for “ambiguity” for us in the question of who the enemy is and what rights we are defending.

Please share what 2022 was like for you. It changed everyone. Why, despite all the difficulties and uncertainty, did you continue to organise the Travelling Festival?

Volodymyr Khanas, photo from personal archive

Already in late February we were helping many volunteer groups, and in March we began to film and document their work. Already then people started asking me in everyday conversations if I could bring a film to watch together. Because volunteers are constantly in working mode, and occasionally they need to switch their focus. Internally displaced people, who were trying to find a community in new cities, also asked to show them some films. People want to watch other people, learn about true stories, reflect.

In addition, our defenders at the frontline often ask us to send them something to watch “about civilian life.” They often have no internet there, so we send them films on USB drives. As I understand it, it’s valuable for them to see what they’re fighting for.

In your opinion, how has the festival affected us in 20 years?

We already have audiences and creators who have grown up together with the festival. These are “children of Docudays,” “grandchildren of Docudays.” Those who grew from volunteers to filmmakers, producers. If that’s not success, then what is?

Moreover, we’re also observing changes in the human rights field. In Ternopil, we’ve been holding Nobel readings since 1991. The biggest discussions used to be around two questions: When a representative of Ukraine is going to receive the Prize? And second, why are there so few women among the winners? When the Centre for Civil Liberties and its head Oleksandra Matviychuk received the Nobel Peace Prize, I said, “We can shut down our readings, because the result has been achieved. The very same Sasha, an activist and a protagonist of Serhiy Lysenko’s film Euromaidan SOS from the Encyclopaedia of the Maidan, an almanack created by Docudays UA! I wrote a card for Oleksandra’s 35th birthday and said that “I’ve finally resolved the question I asked myself about who I’d like to see as the next President of Ukraine!”

Even if this comes off as pretentious, still, the world knows Ukraine thanks to our documentaries. Yes, there aren’t enough of them. Yes, we need to work, yes, we need to look for resources, but that’s how the world learns about us, and that is why working on the international market and bringing our different—I emphasise, different—documentaries to other countries is incredibly important.

How do you see the “image of the future” for the Travelling Festival?

Working on the Docudays UA Park, photo from personal archive

The Docudays UA Park is growing in Dubivtsi. It produced its first nuts this year. It needs another five years for the trees to give shade, we’ll put benches there, and we’ll bring a truck with a large banner for a film screen to the mountain across it. And we’ll sit there, in five years I’ll be even older, we’ll watch films and talk. The whole world will be greeting us on our 25th anniversary, and we’ll be sitting in the cosy Docudays UA Park and enjoying ourselves. People of different ages, from 4 months, because my granddaughter is 4 months old now, to those who are over 90, will be able to watch films there.

There will also be queues of people who will come to the Kremenets Local History Museum to submit their materials to the collections of the Travelling Festival. Our archive will constantly receive new and new talented achievements.

This is my “image of the future” for the Travelling Docudays UA, it’s technological and, of course, peaceful, victorious.

The conversation has been recorded by Ksenia Opria.

The 20th Travelling Docudays UA is held with the support of the Embassy of Sweden in Ukraine, Embassy of Switzerland in Ukraine, US Embassy in Ukraine. The opinions, conclusions or recommendations do not necessarily reflect the views of the governments, charities, or companies of these countries. Responsibility for the contents of the material lies solely on its authors.